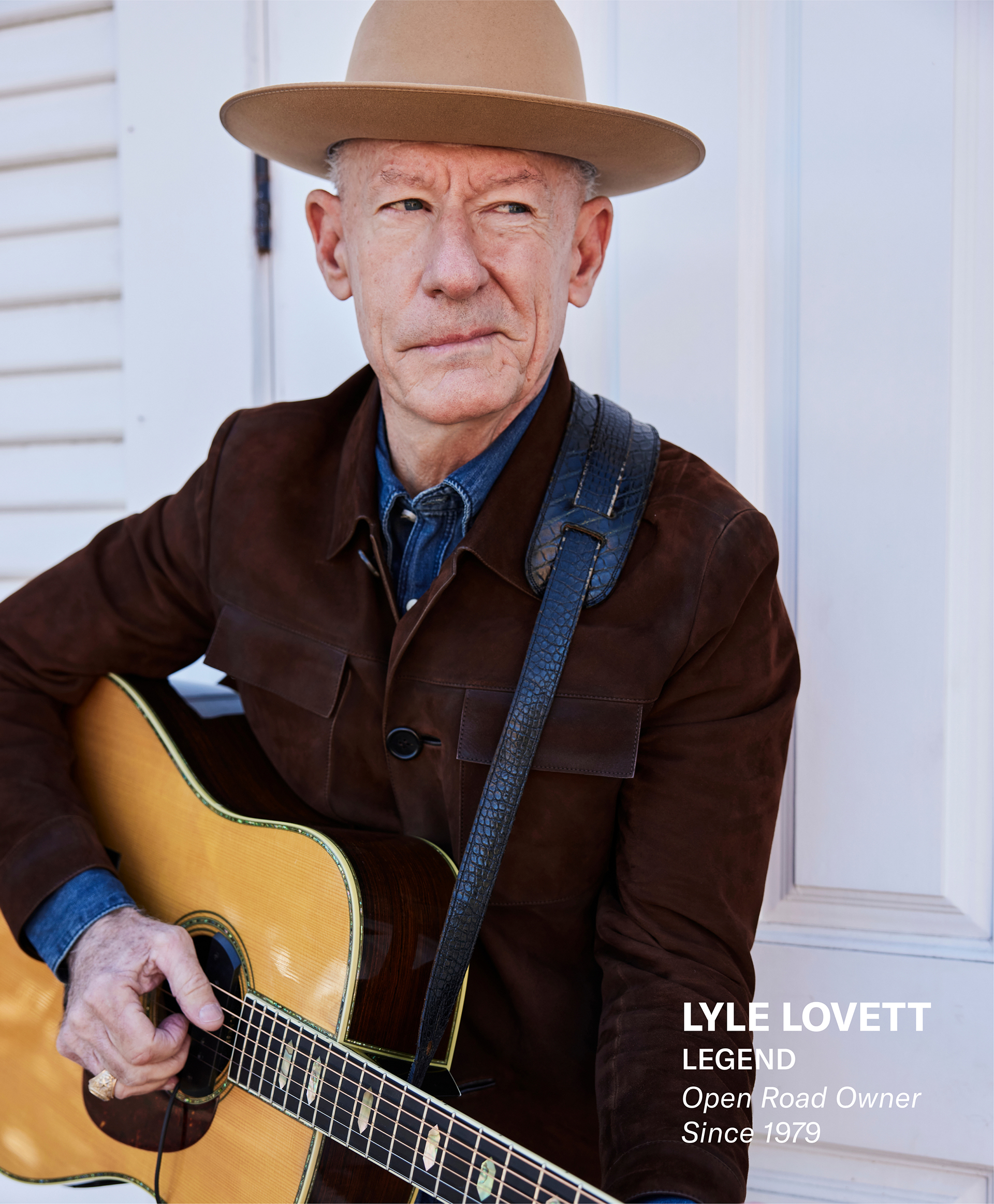

Lone Star State of Mind

LONE STAR STATE OF MIND

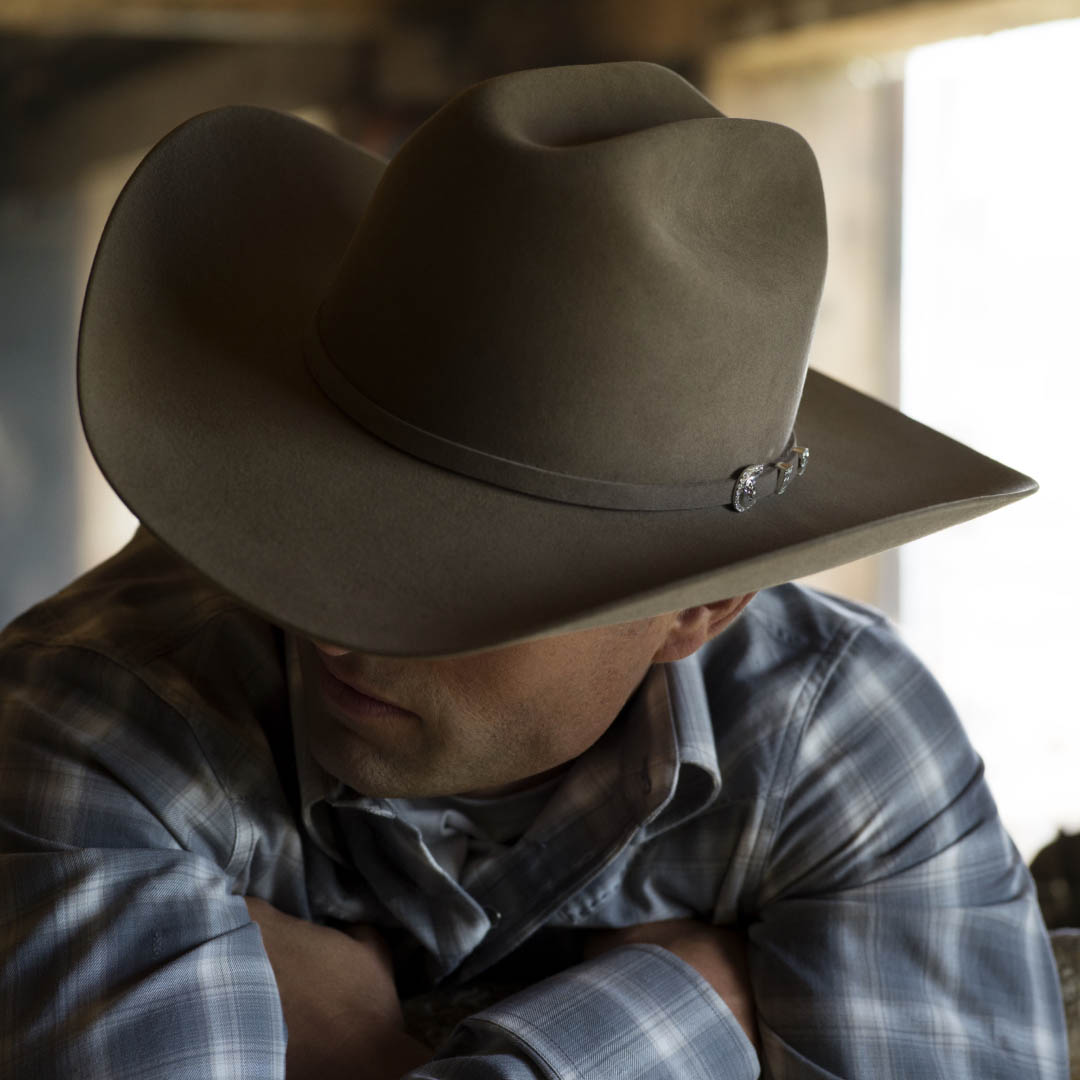

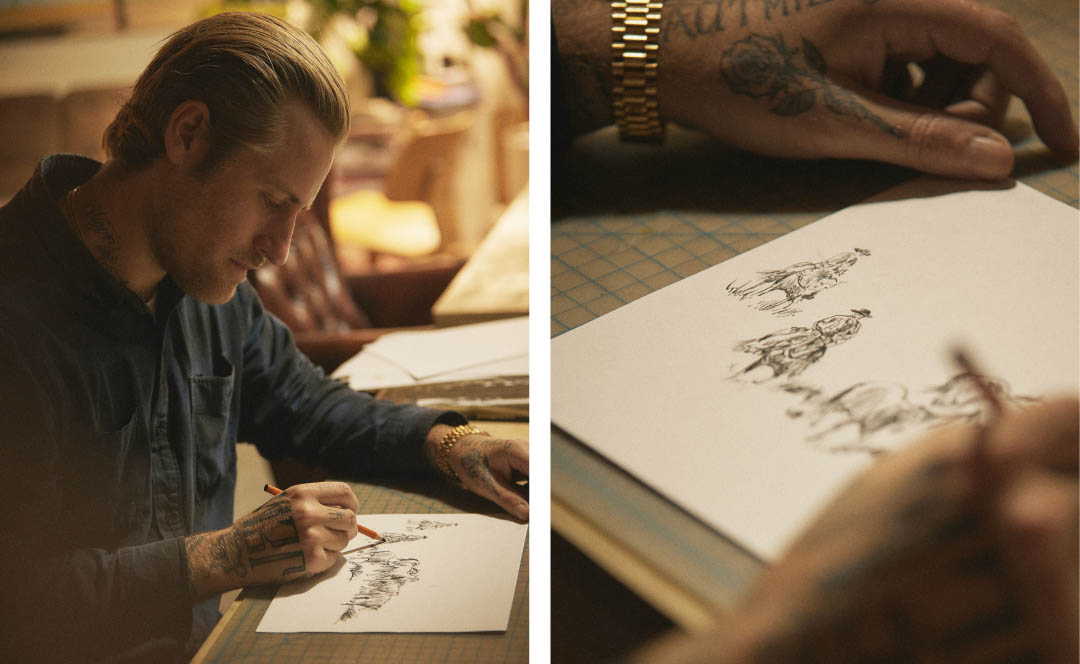

Talking art, inspiration—and Stetsons—with Texas

artist Jon Flaming.

Photography by Tyler Ellison

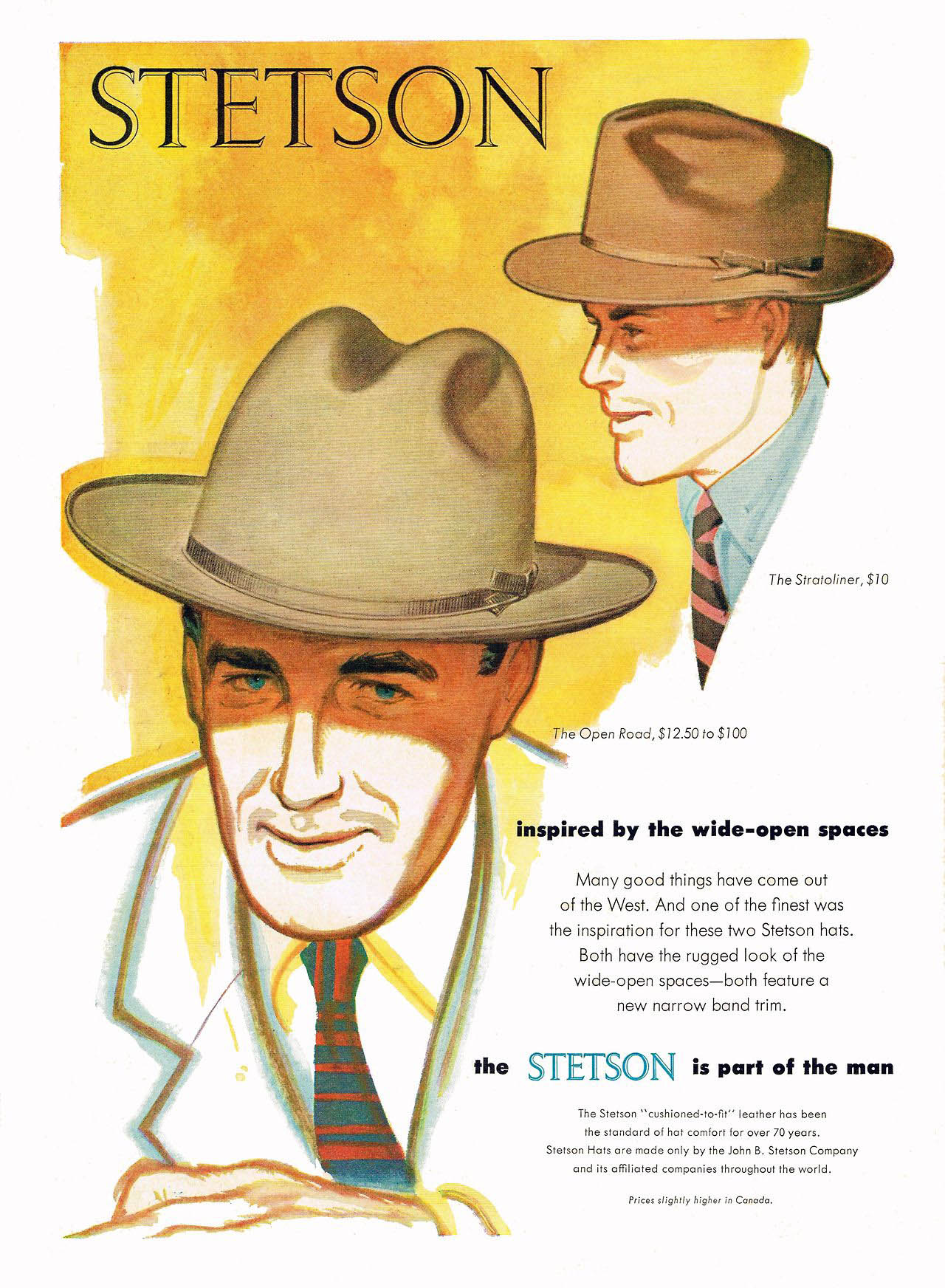

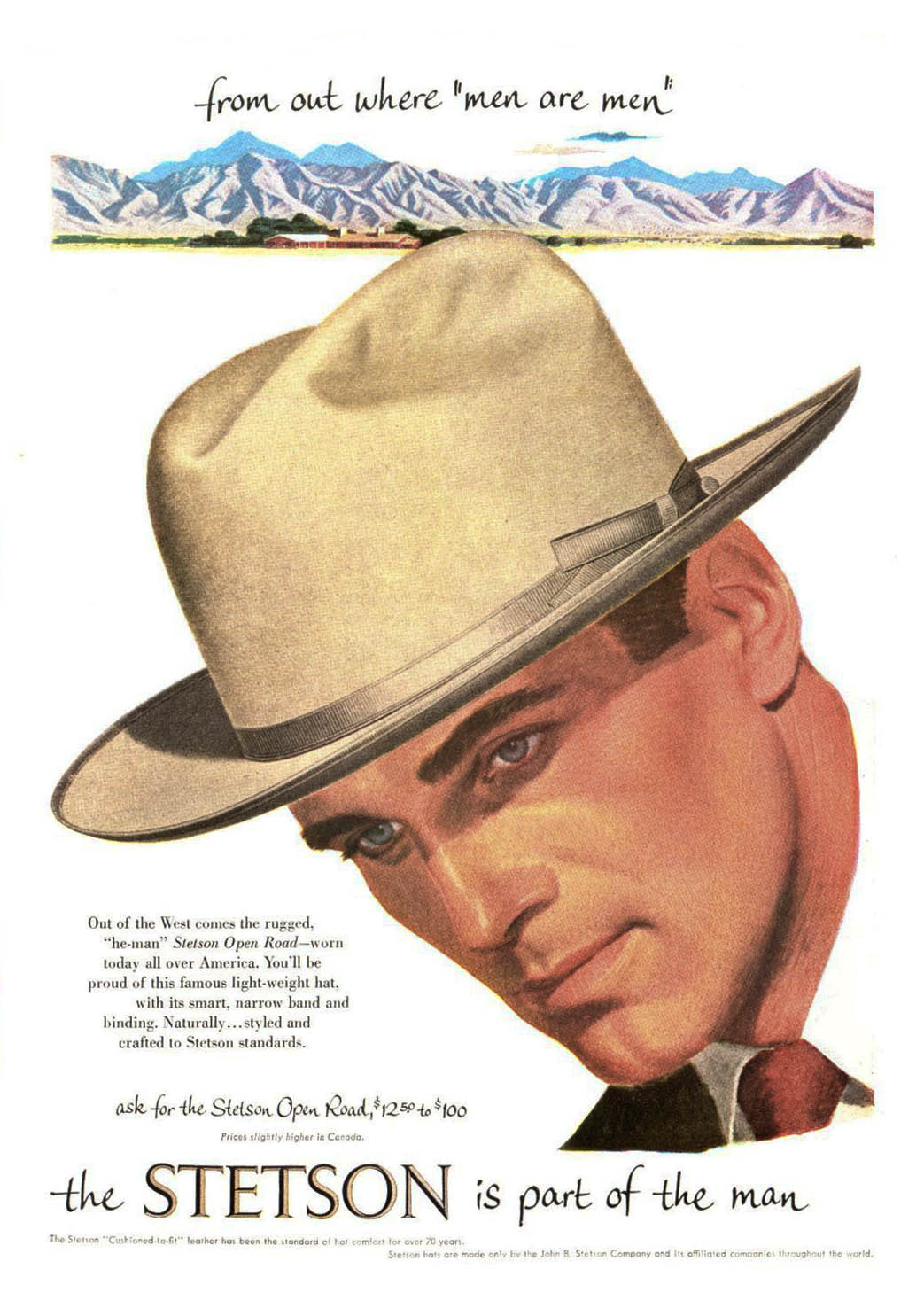

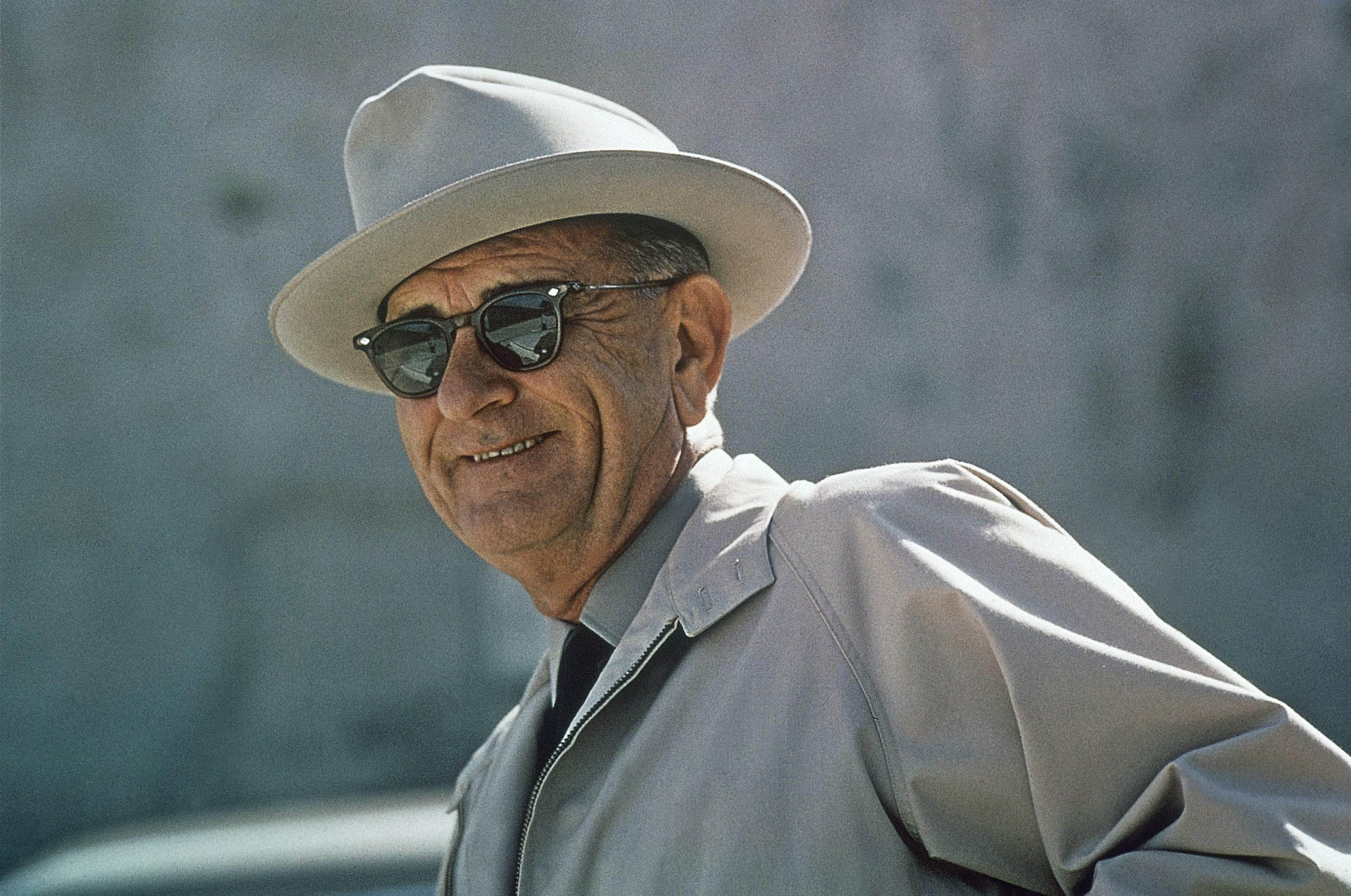

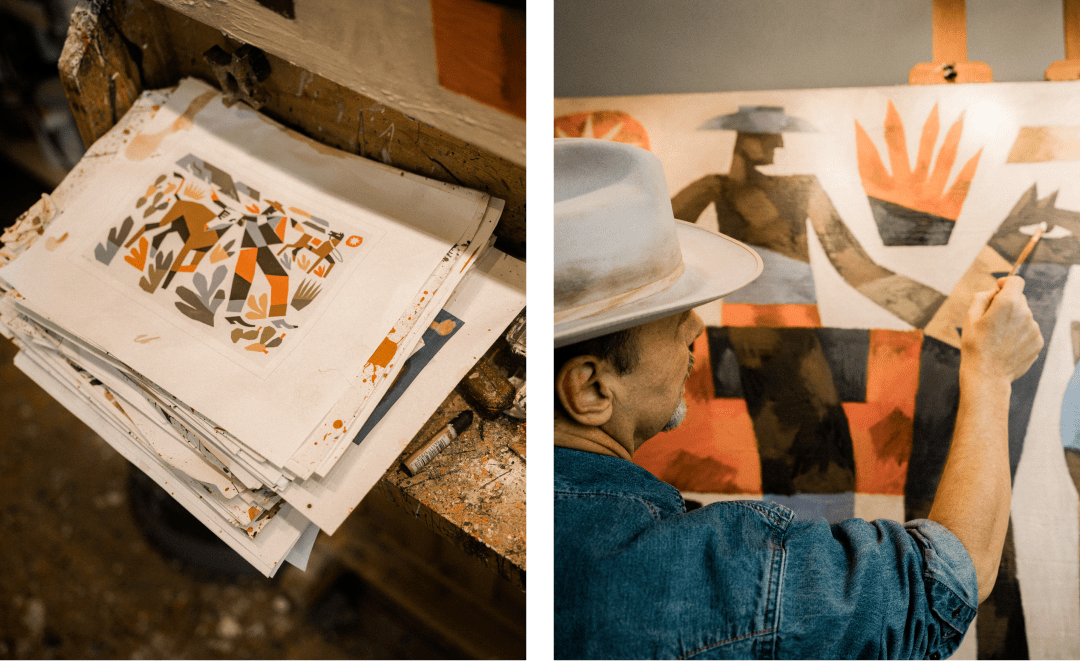

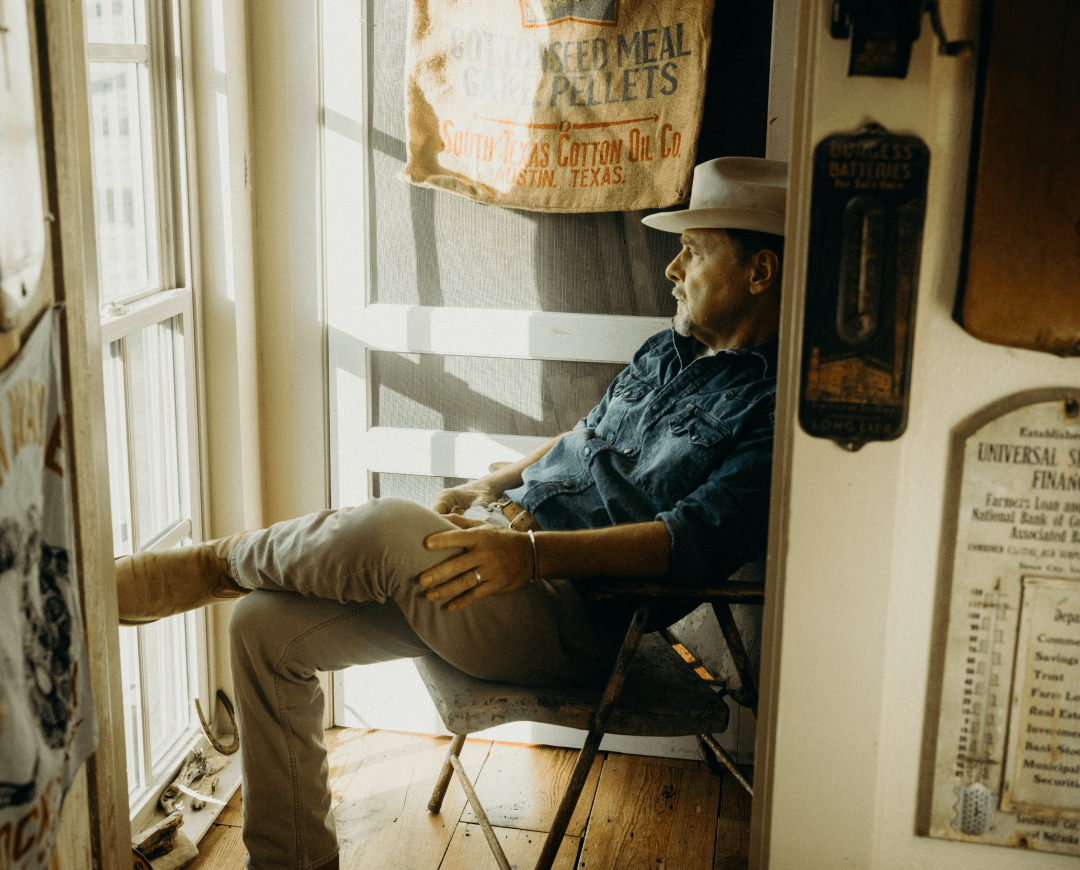

Artist Jon Flaming is no stranger to Stetsons. He’s worn them since at least the ‘80s and often dons one for portraits and publications, reminiscing fondly on a collection of hats his granddad wore way back when—whether to church, to the bank, or just in town in general. And then, there’s the work: cowboy hats are a frequent motif in his paintings, sketches, and assorted other pieces.

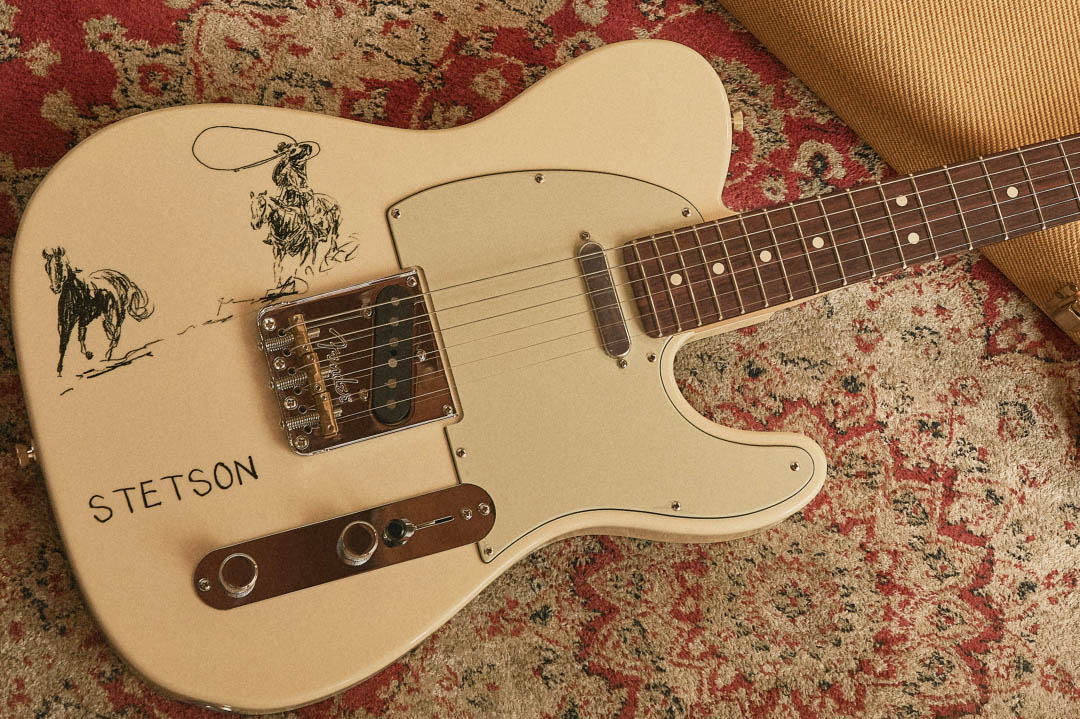

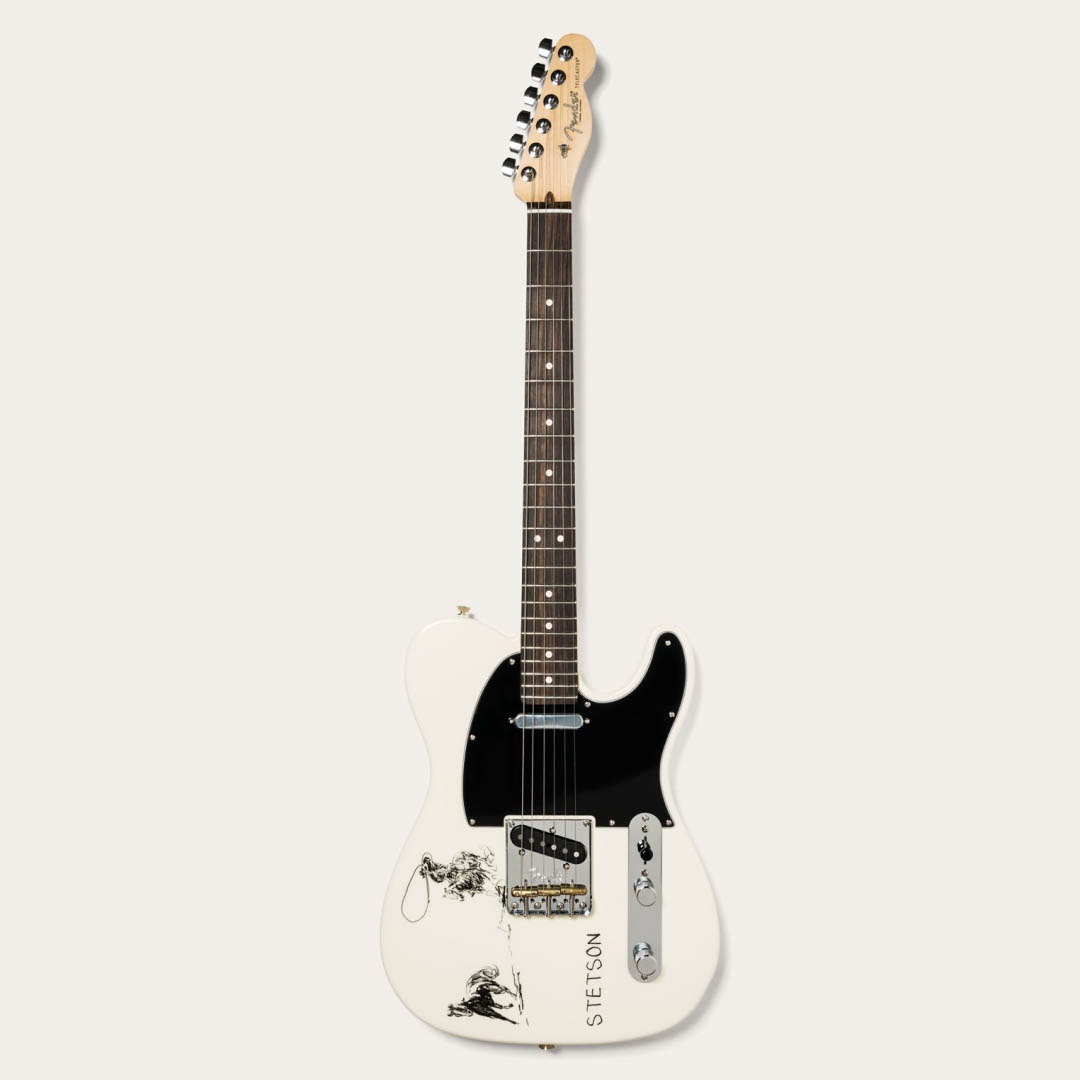

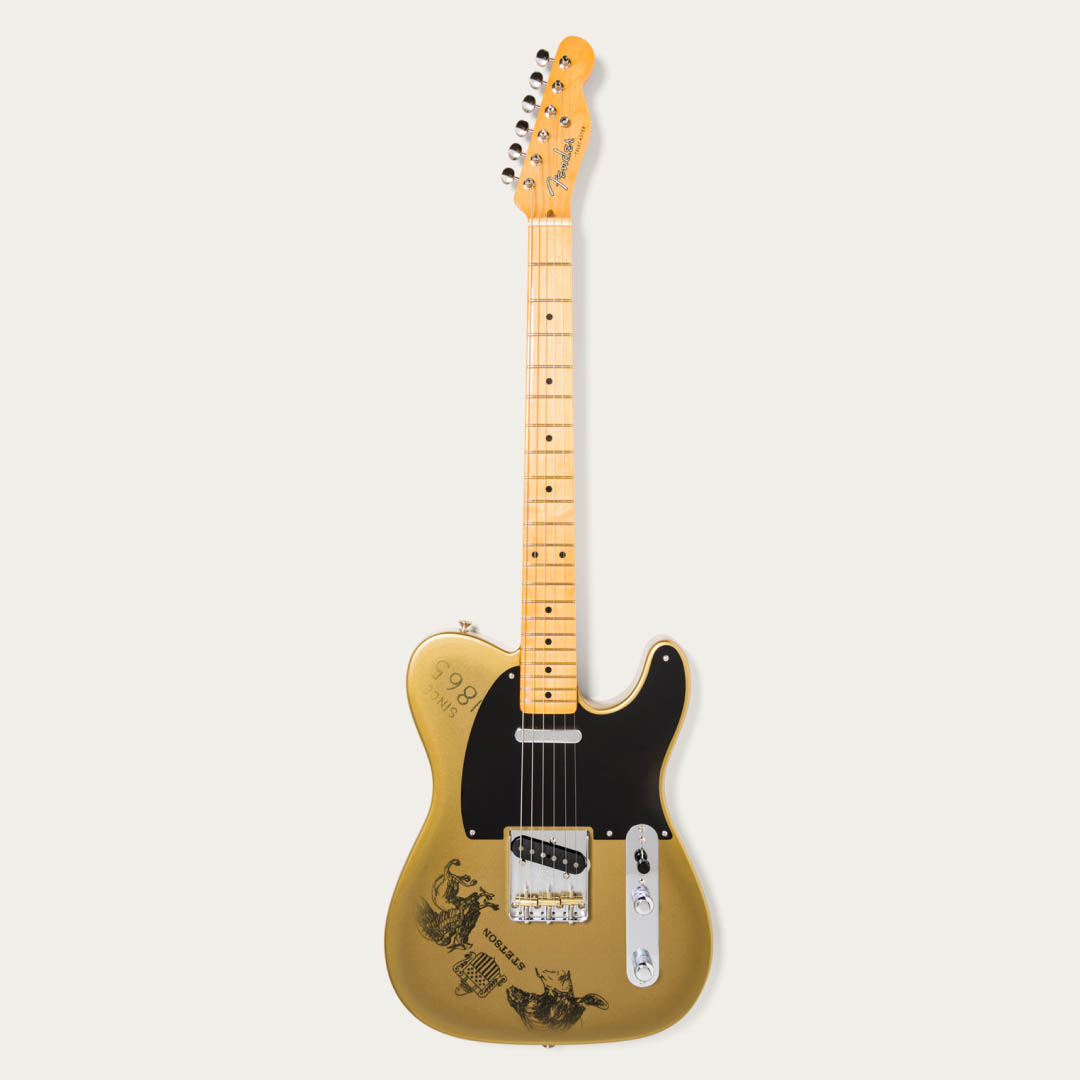

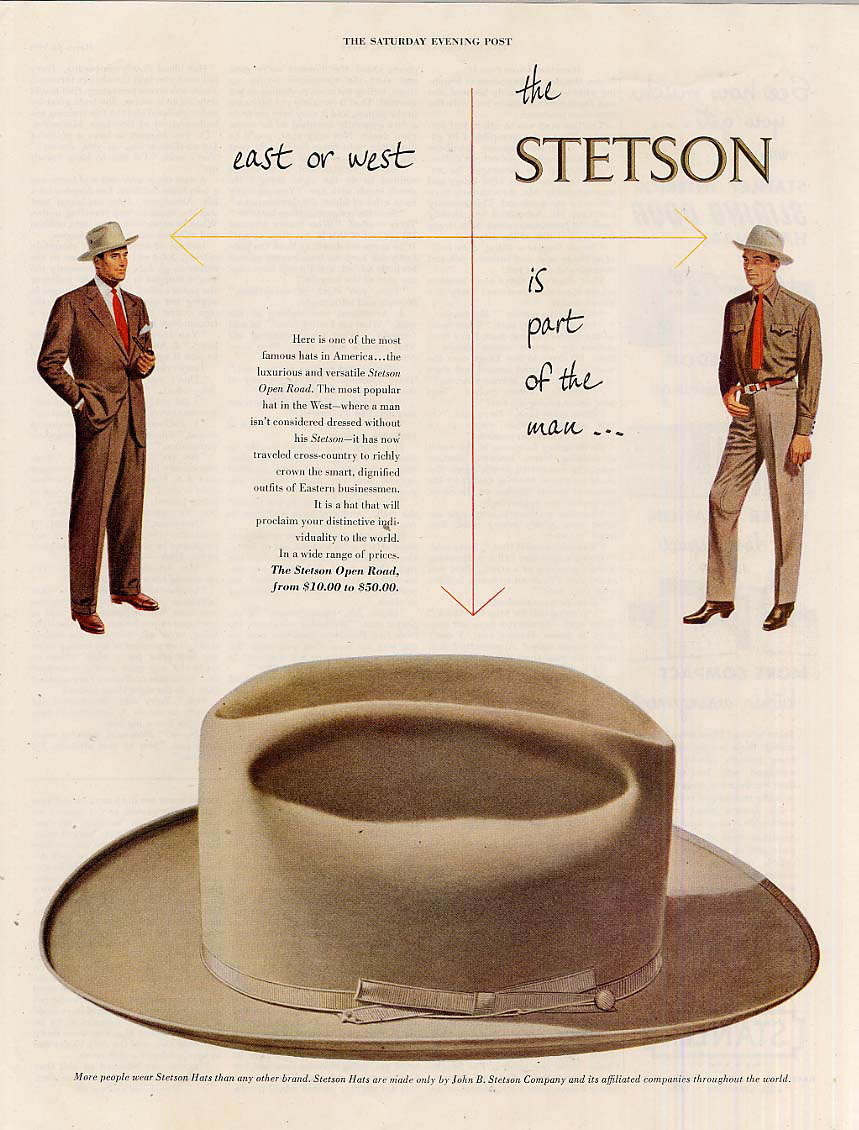

But the relationship took on a new dimension due to an Instagram post last April: a fine art print depicting the iconic Stetson Open Road, situated amongst the familiar sights along the literal open road of Big Bend, the National Park in West Texas. The image drew the notice of his many fans and collectors, along with those of us at Stetson.

It’s the latest step in an artistic journey that began when Flaming was 5 and noticed a kid in Sunday school drawing an ultra-realistic jet next to him. This was at the height of the Vietnam War, he notes, when “those types of things were top of mind subject matter for little boys, and I was like, ‘Man, that is such a cool jet airplane. I wish I could draw one like that.’” He jokes now that his whole career has been in pursuit of drawing that cooler airplane.

“It’s modern, but it’s also primitive. It’s folk art. It’s graphic. It’s this mixed bag of influences.”

This happened when he still lived in Wichita, KS where he was born and where his grandparents had a 2,000-acre ranch nearby. His parents were musicians, however, and desperate to leave the Midwest in those days, so they ended up in Irving, TX, just outside Dallas, where he encountered a neighbor’s coffee table book illustrating the history of art, which further inspired him. Bypassing fine arts training for design and advertising, he ran a design studio for 25 years, creating work for clients like Sony, FedEx, and American Airlines.

His artistic aspirations never left him, however. Soon he was creating pieces in his off hours that reflected his newfound home and memories of the ranch (which, by the way, is still in the family) filtered through his signature graphic style. “Like a Texan moseyed into an old Works Progress Administration poster, lit up a cigarette, and stared into the future” is how one observer memorably described it.

It’s a style all his own, one that he developed over the years, drawing from influences such as Matisse and Picasso, graphic designers like Paul Rand and Saul Bass (best known for cinematic title sequences including Psycho and The Man With the Golden Arm), Texas artists like Everett Spruce and William Lester, and Jerry Bywaters. “It’s modern, but it’s also primitive,” he says. “It’s folk art. It’s graphic. It’s this mixed bag of influences.”

The art has drawn the interest of the set designer for, let’s say, a popular television series set in the West, which means Flaming’s creations might soon make a cameo in the show. “At 60, I don’t count my chickens ‘til long after they’re hatched,” he says cautiously. “I’ve just learned that things come, and things go, and things fall apart, and things happen you never thought were going to happen.”

As with the open road itself, it’s all about the journey.