The Navajo-Churro Shepherds

This story is meant to be a small glimpse into the life of Navajo shepherds and pay respect to the sacred relationship between the Navajo people and their Navajo-Churro sheep. It’s commonly said that one must be Navajo to truly understand the depth of this sacred bond and what it means among families, clans and on an individual level. For that reason and more, this story was told by the shepherds themselves.

By Heath Herring and Leney Breeden

“Take care of the sheep and they will take care of you.”

These words resonate across the Navajo Nation, cutting straight to the core of what it means to be a shepherd. They symbolize the relationship between the Navajo-Churro sheep and the Navajo people. These shepherds, along with their flocks, have all been affected by the drought that has plagued the Southwest in recent years. But despite the hardships, this way of life is filled with harmony, peace, and beauty.

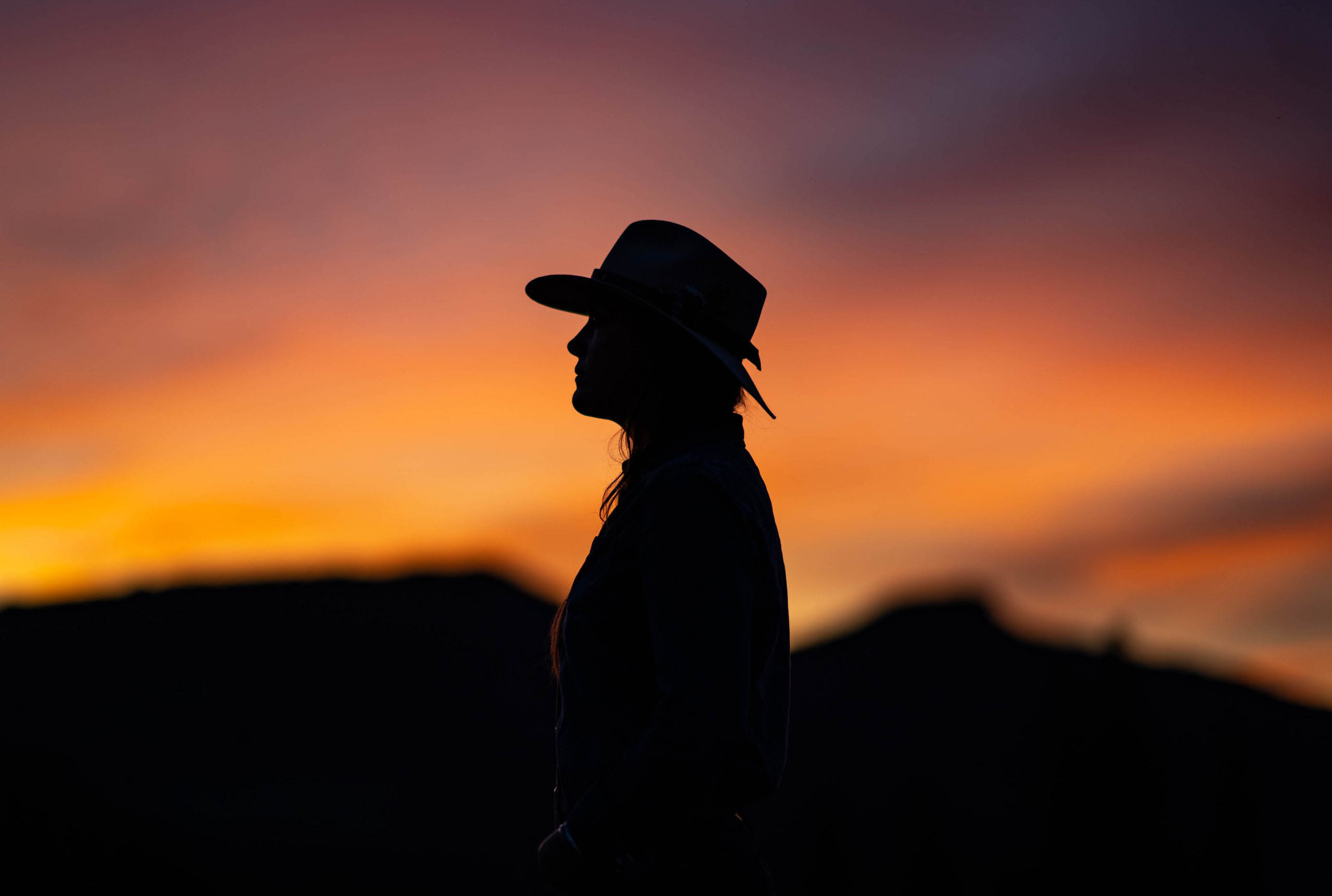

Colby is a young shepherd outside of Sawmill, Arizona in an area called “Che’chiltah” meaning: “Among the Oak Trees.” He has a flock of Navajo-Churro that he raises with the help of his family.

The Navajo-Churro is a rare, endangered breed of sheep commonly thought to be adapted from the Churra, which were carried to North America by the Spaniards over 400 years ago. Because of this adaption, the Navajo-Churro is incredibly acclimated to the desert conditions of the Southwest. It has the ability to thrive in conditions where other breeds would likely perish. It has a unique, two-part fleece, unlike other sheep breeds that only have one. The fibers are long, lustrous, low in lanolin and take natural dyes readily. The result is a strong, beautiful yarn that has been spun and woven into many traditional Navajo weavings for centuries.

“The story is that the holy people took down the clouds for the sheep’s body, willow branches for the legs and crystals for their eyes. It was just a statue until they breathed life into it. Then it was alive. The sheep was quiet, so they put the thunder inside it and gave it a spirit and a voice. The sheep are sacred, that’s what I see when I look at Navajo-Churro. The Land is wild and they match it. They have a unique spirit. You can feel it. They put life back into the earth.“ — Colby Yazzie

Drake Mace is a Shepherd who creates beautiful, traditional weavings and spends every day tending his Churro flock in Chaco Mesa, New Mexico.

“Churros are resilient and flighty. Which is good when they’re on the range because they’re alert and can flee from predators. They’re also excellent mothers. They take care of their lambs even when it’s raining or snowing. A lot of the fine wool breeds will just abandon their lambs or leave them to freeze in those conditions, but Churros won’t do that. They’re good sheep to have.” — Drake Mace

“In Navajo, we say ‘Dibé be’ iiná’ which means ‘sheep is life’. We live off of the sheep. They provide us food, sustenance, wool— everything. A lot of shepherds live by that saying. The sheep are a big part of our history. I’m with my sheep every day. From morning ’til dusk. As Navajo, we talk about Hózhó, meaning harmony amongst everyone and balance between all living things. That’s what my life with my sheep brings me.” — Drake Mace

Kelly Skacy is a shepherd in Northern Arizona. Her flock of Navajo-Churro has been with her family for generations. Kelly came to learn and love this way of life through everything she was taught by her father, Herbert, who still works alongside her to this day.

“The sheep hold us to our land. They are the reason we remain close to it. Because of them, we see every sunrise and we never miss a sunset. It is because of our sheep that we still hold on to our reservation. If we lose them we will lose our land.” — Kelly Skacy

Eliseo Curley is a shepherd, weaver, and educator in Shiprock, New Mexico who’s been raising his own Navajo-Churro for about six years. Every Spring he hikes 20 miles into the Carrizo Mountains, alongside other shepherds and their flocks, to take their Churro to a sheep camp for cooler weather and better grazing during the warmer seasons.

“What I like about this way of living is having the freedom to do what you want. You’re not being controlled by a 9 to 5 job and stuck in the same old routine. With this lifestyle, you don’t always know what you’ll do in a day. You wake up, cook breakfast and then an hour later you’re out harvesting wild tea somewhere. Next, you’re going to a ceremony, weaving, visiting the sheep camp, or maybe even teaching classes the next day. It’s spontaneous, and that’s what I like about it.” — Eliseo Curley

Many shepherds speak of this life being handed down from their grandparents. It’s predominantly instilled by their grandmothers, as Diné (The Navajo people) are historically a matriarchal society.

“My grandparents always had sheep. When I was around 8 years old, I would help take care of them, shearing them when it was time to shear, then following as they herded the sheep. So a lot of this I learned at a young age.” — Eliseo Curley

“My grandmother always said her sheep were her mother and her father because they were passed on from generation to generation. She would tell us ‘they’re your mother. They’re your father. So take care of them like they take care of you.’” — Drake Mace

“I chose Churro sheep because my grandfather passed the herd onto my dad. So I look at it as holding onto what my grandparents had and continuing that legacy. My Dad says, ‘when you have livestock you have to work right beside them.’ I am a strong believer in working for what you have. I’m down here every morning, rain or shine. You have to do what you can, by all means necessary, to help them in whatever conditions you’re in.” — Kelly Skacy

“I chose Churro because I love the versatility of the wool and how it’s variegated throughout my weaving. Red, brown, grey, black and white. I love the natural colors. There’s a lot of designs you can create with just four colors at the most. I used to use a lot of processed yarn until I fell in love with spinning my own wool.” — Drake Mace

These pieces are not only works of art, but handwoven stories of a people and way of life. They communicate strength, intention, and endurance in a way that fully utilizes these multi-faceted sheep that hold so many gifts. These weavings are also a tangible representation of a slower, thoughtful lifestyle – a powerful message to an otherwise fast-paced world.

“Weaving is something I’m really passionate about. It’s an aspect of the sheep life that I love so much, and it ties me to my history.” — Drake Mace

While many shepherds speak of peace and harmony with the land, the sheep and one another, most agree that this can be a hard way of life at times. Mother Nature calls the shots. Ongoing drought, remote locations, limited resources, and grazing conditions can be financially strenuous for shepherds on the reservation.

“It’s hard living on the reservation. We don’t have access to a lot of stores, and all the border towns are 50 plus miles away. We live completely isolated. So living on the Rez can make you a very strong individual. There are rough patches in life but you just gotta stay strong and positive and persevere. Have goals. Stick to your guns. Be yourself. Live your life every day, and be grateful for what you have, instead of moping around about what you don’t have.” —Drake Mace

“I wish more people had an interest in preserving old ways. Those ways got us through so much. They got us through The Long Walk, through the livestock reductions and through hard times in general. Every single day that we go through, the animals get us through it. I think it needs to be stressed that it’s very important.“ — Colby Yazzie

“Despite not always being financially stable, you will always be rich in your life with your livestock and in the things that you know.” — Eliseo Curley

A lot of the hardship on the reservation can be attributed to the drought that hinders plant growth on the rangelands for the livestock to survive on. The lack of plant life forces shepherds to purchase hay, the prices of which have been rising. The hay has to be shipped in from further and further away because it’s unable to grow substantially near the reservation.

“The drought has affected us in many ways. We used to run about three to four hundred head of sheep, but we had to cut back to about 120. We use hay and supply sheep with nutrients during these conditions. I think a lot of people lose their herds because of the drought. They can’t afford hay so when there’s no feed, grazing is all they depend on. It feels good to have some rain around here this Spring.” — Kelly Skacy

There was a small reprieve during the Spring, but there’s no telling how long it will last. Especially with the upcoming heat and summer wind which could cause everything to dry out again.

“My main goal with the Navajo Churro is to help my family and others and help to supply them with resources.” – Colby Yazzie

“My hope is to carry on the traditional knowledge and pass it on to younger people, or even people my age, who are out there wanting to learn. That’s what keeps me going – teaching other people what I know. Which can take me places to talk to others, not just on the reservation but across the country. This way of living doesn’t keep you in one spot. You’re helping people all over the place. That’s what I enjoy.” — Eliseo Curley

“If I won the lottery tomorrow, I would buy a nice spread of land, and just do what I do because it’s what I love. I’m just happy to be amongst sheep. “ — Drake Mace

“This is the way of life that I want to live. I love being a shepherd. You don’t get the same day twice. Doing this and being here makes me happy and there’s nothing else I would rather do. To me, it’s carrying on a legacy. Not everyone sees the value of the wool, to me it’s everything.“ —Kelly Skacy

In addition to this way of life, the Navajo-Churro sheep are also raised and protected by others who wish to see the breed flourish. Navajo, Hispanic and Anglo shepherds and producers alike all work hard, often together, to protect and help perpetuate the growth of this breed and increase awareness about its endangerment, cultural significance, and invaluable qualities as a sustainable breed. The Churro are incredibly resilient, as are the shepherds who raise them, but nature isn’t cutting anyone any slack. There is currently a serious need to continue raising awareness about drought conditions in the Southwest and the impact it’s having on shepherds and all agricultural life throughout the region.

For more information about Navajo-Churro sheep visit: navajolifeway.org and navajosheepproject.org

Special thanks to Kody Dayish