HOMETOWN HEROES

From the rodeos of Okmulgee to the runways of Paris, a new generation is preserving the legacy of Oklahoma’s Black cowboy culture and blazing new trails for its future.

By Andrew Bradbury

Though one in four working cowboys in America was Black after the Civil War, their stories, and their efforts in shaping the frontier and the sport of rodeo were nearly absent when the history of the West was first written. A movement of rediscovery that’s been brewing across the country for a few decades, has found fresh momentum across the virtual frontier of social media where a new generation is bringing more visibility to Black cowboy culture than ever.

Meet the Oklahoma Cowboys. It began as a lone Instagram account @oklahomacowboys, founded by Oklahoma City-based artist and photographer Jakian Parks, as a way to celebrate the rodeo life he was introduced to through his late aunt, Shay Nolan. It quickly attracted 125K followers from nearly every corner of the globe, including the world of high fashion. It’s since evolved into an editorial and cultural platform, as well as a charitable foundation that’s teaching horsemanship to the state’s inner-city youth.

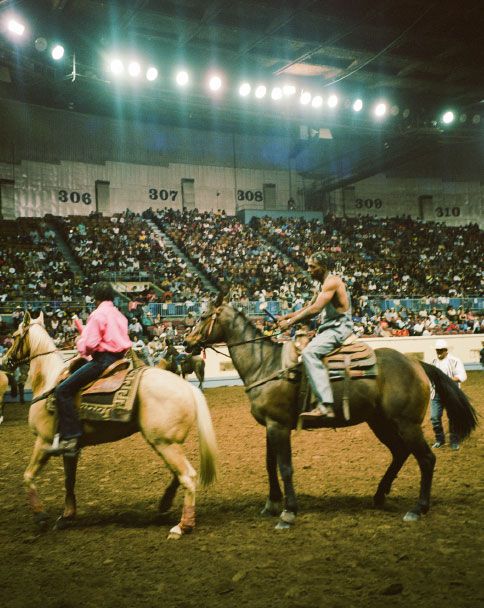

top: Riders at the Okmulgee, OK rodeo, captured by Gagan Moorthy. bottom: Two portraits of Oklahoma cowboys, captured by Jakian Parks.

Through original and shared content, their online account offers a kaleidoscopic vision of Black cowboy life. Says Parks, “I am deeply inspired by black community and societal storytelling. Capturing the essence of pain, beauty, progression and prosperity creates narratives that only images can properly convey.” That range of emotion can be seen in the Oklahoma Cowboy posts, like a behind-the-scenes rodeo clip that shows a rider cracking jokes before smash-cutting to his harrowing bronc ride.

The account also offers a look at how western fashion is truly styled by the cowboys of today. When asked, Parks is unsurprised that western style is more popular than ever. “As the look grows, people realize how powerful and intuitive western workwear is,” he says. The Instagram fame netted Parks an invite to Paris, where two faces of Oklahoma Cowboys, Taylor Williams and Ronnie Davis, walked the runways for Pharrell’s western-inspired Louis Vuitton show.

Williams, who also appears in Stetson’s Fall ‘24 Western campaign, was born in Tulsa and has been riding horses ever since he can remember. “My grandpa rodeoed and my dad rodeoed so when I was born I was always around it,” he says, “I met Jakian at a rodeo and he wanted to take a picture of me. This was back when the account had 100-something followers. Now it’s a big platform,” he says. For Williams, “it’s great to carry the tradition of being a black cowboy, being that the word cowboy came from black men. And it’s crazy that people don’t know that.”

Oklahoma cowboy Taylor Williams for Stetson’s Fall ‘24 Western campaign, captured Richard Phibbs.

On a recent trip to Oklahoma’s Boley Rodeo, which was founded in 1903 and is the oldest and largest African-American community rodeo in the country, Parks captured its heart-stopping Pony Express race. “It’s one of the most jeweled events of Black cowboy culture,” Parks says, “a competitive eight-man relay race that’s a people’s favorite at Oklahoma rodeos and always evokes enthusiasm and togetherness in the stands.” For Williams, there’s a special connection to the event. “My grandpa invented it.”

While Black cowboy history may run especially deep in Oklahoma, it’s one that many of the account’s followers were unaware of. Variations on the phrase “I had no idea there were Black cowboys,” that have appeared in the comments are proof that their intention—to document and celebrate—is an essential one.

“Yes, Black cowboys really do exist in Oklahoma City. It’s their whole life and lifestyle, they have land, they have livestock,” says Chloe Flowers, who serves as editorial director for the Oklahoma Cowboys and its foundation, “one of the most important shifts we envision is an expansive display and rediscovery of black equestrian history. Bringing awareness to African-American agriculture and the stories of our ancestors is the starting point for a cultural movement.”

The Pony Express race and the Oklahoma Cowboys flag, captured by Gagan Moorthy. A moment in the ring, captured by Jakian Parks.

This movement towards rediscovery is not isolated to Oklahoma. Across the country, by-Black, for-Black rodeos like the Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo and the Texas Black Invitational Rodeo were founded as part of that effort. City-based groups from the “concrete cowboys” of Philadelphia’s Fletcher Street Urban Riding Club and the “Compton cowboys” of the Compton Junior Equestrians have shown that Black cowboys aren’t just confined to rodeos and ranges. Their stories are being told in new ways in different mediums by artists like the painter Thomas Blackshear and filmmaker Jeymes “The Bullits” Samuel.

In the summer of 2024, the Oklahoma Cowboys foundation’s mission (a four-pillar initiative focused on education, preservation, agriculture and outreach) began having real-world impact, offering its first youth summer camp. During the week-long immersive camp, kids with no exposure to ranch life were taught the principles of horsemanship—and picked up a little cowboy confidence along the way. “There were kids who were scared to ride a horse on day one that were jumping up and killing it by day four,” says Flowers. They were also taught some classic cowboy values. “Essential qualities a cowboy should possess,” says Flowers, “are respect, dedication, consistency, chivalry, integrity, courage and fortitude.”

The foundation will offer similar camps in the future as Oklahoma Cowboys continues to expand its efforts in the local area and its presence on the rodeo circuit, embodying the hashtag it often uses to punctuate its posts: #WeAreCommunity.

The Oklahoma Cowboys inaugural Youth Summer Camp, captured by Jakian Parks.

Follow the adventures of the Oklahoma Cowboys on Instagram @OklahomaCowboys.